By Brennon Land

I’ve always been a good worker. It’s a strange trait—like I’ve got to prove that I deserve every bite I get to eat. Should probably talk to a therapist or something about whatever childhood trauma led to that mentality, but I stay too busy to ever schedule an appointment. Besides, there’s nothing more American than working until you drop, and I haven’t dropped yet. Even those times I feel like I’ve come close, there’s this deep reserve of pride and spite that always seems to keep me on my feet. I don’t really even know who I am if I’m not working. That’s why I had to get a job, any job, as soon as my daughter turned three. I love spending time with my baby, but I make a terrible housewife. It just feels unproductive. Cleaning the same messes over and over again but the house is never really clean. There’s always dirty socks crammed in between couch cushions or a random plate left on a bookshelf or somewhere else it has no business being.

Spending all day cleaning and then sitting down at the end of the day only to discover that you were so busy cleaning up the same little messes you picked up after yesterday that you haven’t had time to sort and clean laundry so your kid is wearing mis-matched socks all the time and your mother-in-law is high-key judging you, but you really have nothing left but a philosopher’s understanding of human futility and an existential crisis because nothing even matters and at least the kid’s socks are clean, right?

That ain’t living.

So, I got a job as a barista at the coffee shop they put in the new community center on base to pay for daycare so I can have a little alone time on my days off to work on finishing my online degree and maybe even contribute a little something-something to the household account so I don’t seem like some sort of “dependa”. It’s not a real barista position, it’s a Starbucks affiliate and there’s no craft at all to the corporate way to make a latte. Just punch a button for espresso and pump way too many squirts of syrup into a cup and smile real nice while you’re at it and voila! It wouldn’t exactly get me hired at a real coffee shop, but I’m enough of a coffee snob to know I’m slinging crap brew and I have figured out a few tricks to make the coffee pass for something semi-decent. The customers seem to like me. I get tipped well, but I suspect that’s got nothing to do with any appreciation for my superb service.

They actively bitch about my co-workers, both to me while I make their magic bean water and in the formal complaints they write on comment cards that get relayed up the base’s Force Support Squadron chain of command. And yet, despite all the complaints and vague reprimands from our manager, the other baristas still generally take home the same amount in tips I do—I know this only because the daily credit card charges are logged in a spreadsheet we all work out of. I know for a fact I could never get away with being rude and serving burnt shots. I can’t even be slightly inattentive without seeing a dramatic drop in my tip amount. I have had to deliberately practice an approachable resting-server-face because I can’t afford for people to think I have any kind of attitude. Gotta be happy about my job, say yes to every ‘opportunity’ and visibly outperform my coworkers who can’t be bothered to mop the syrup-covered floors at the end of their shifts just so I can’t be accused of slacking off. Because nobody likes an “affirmative action” hire collecting a paycheck that they didn’t break a sweat for. Especially one paid by your tax dollars.

So, I work my ass off for $12 an hour, plus tips. I clean the messes left by the shift before me, without complaint. I draft checklists and step-by-step guides for future new-hires. Smile and nod when my coworkers talk about getting their nails done every weekend, while hiding my short cropped and working-class hands that are cracked and dry from washing dishes between customers. On really slow days, I wipe down all the tables and chairs in the lobby. “If you have time to lean you have time to clean” is the mantra I picked up as a teenager at my first customer service job. I even volunteer for other shifts at the movie theater and the bowling alley. All of these facilities are under the same chain of command, and customer service employees are pretty much interchangeable.

That’s how I ended up out at a campground forty-five minutes away from the base. I learned the point-of-sale system that only one other person up in admin—who gets paid probably double what I do—knows how to operate and they needed someone to come out and set up the register at the snack shop and outdoor rec rental service. Since that didn’t take long, and I couldn’t be seen sitting around waiting for my shift to end, I started helping with other random tasks. Repair a screened-in porch at one of the cabins? Sure, why not? Turns out, leadership likes that kid of initiative, especially from a civilian. They asked me to keep working at the campsite for a couple of weeks to help get the place cleaned up. I could even stay out in the caretaker’s trailer if I wanted, so I wouldn’t have to make the hour and a half round trip every day, but I couldn’t stay away from home like that. My husband wouldn’t know what to do with our daughter, who already tries to block the door and keep me from going to work whenever she sees me put my black polo shirt on.

It’s nice to be miles away from the coffee shop and the whole base, really. The lake is beautiful. The cabins are cute, and fixing them up is instantly gratifying. And there’s no customers to deal with yet because it is spring and the snow hasn’t yet melted in the shady areas, even though all the birch tree branches are covered in bright, yellow-green buds. We have to be careful not to wander too far because the military outdoor rec space is surrounded by private property, and out a couple hours north of Fairbanks you don’t want to accidentally trespass. But otherwise it’s a pretty sweet gig.

Today’s task is cleaning up the boat house with a couple of seasonal workers. It sounds like the bougiest thing I could be doing out at a lake—hanging out in the boathouse all day—until we open the door. Ten outboard engines are lined in two rows that take up about a third of the floor space. Life jackets of all sizes are piled on rudimentary wooden shelves. Kayaks and paddle boards take up the majority of what’s left after the mass of life jackets and random junk stacked throughout the space. The florescent bulbs overhead cast a mop-bucket grey light that flickers constantly, dirtying everything it touches. Or maybe it’s the layer of dust so thick that I can smell it from outside.

There’s one window, half-hidden between boxes and an air compressor. I head straight for it, hoping to open it and let some air in. Near the window is a scattering of leaves that must have been blown in last fall when the boathouse was being packed up for the winter. Not leaves. Dead butterflies. About a dozen of them, most with their wings folded so you can only see the underside, which has a crinkled greyish-brown pattern like dried leaves. They lay completely within the square of light coming from the window. Something about the scene makes my chest ache. It’s more than unsettling. I can almost picture what happened.

As caterpillars, they must have found shelter in the warm, dry boat house and made their cocoons to wait out the harsh winter in comfort. At some point in the past couple of weeks, they fought their way through the hardened armor that had sheltered them, pressing the excess fluid from their bodies and wings as they emerged in the glowing golden light of the spring sun. They rested, slowly fanning their wings, reveling in the wonder of their new forms. Then, in a glorious test of their lovely new appendages, they rose into the air and floated toward the light and the lake framed by the whole world just outside the window.

Then they ran into the glass.

So, they tried again. And again. In the orange glow of their first sunset, they fluttered impotently against the invisible barrier that separated them from life. How long did they struggle, before they began to fall? Hours? Days? In this dusty, dark room, surrounded by things unused and forgotten, they battered their delicate bodies in hopes of eventually making it through to the other side. There are a few that managed to spend their final moments on the window sill, but most seem to have given up when they hit the ground. They all creeped their way into the perfect square of light and died with their heads pointed toward the sun.

The sight is a picture of decaying beauty that I can’t bear to look at. The cruelty and desperation of their short lives. The futility of their attempts to escape. It’s more than unsettling; it’s overpowering. Like I can hear them all talking at once—if butterflies could speak in the first place—and the only words they know describe injustice of their coming into being in a world such as this.

I comment on the eeriness of my find with a shudder. One of the others, a young woman who gets her nails done every weekend, glances at the wretched scene and responds with, “Gross!” before leaving to find something more civilized to do for the day than mucking about in here getting dust and who-knows-what-else under her pristine French tips. I get to occupying myself with organizing boxes on the other side of the room—as far from the ghost butterflies as I can go.

But I can’t escape their presence. Every few seconds, I’m glancing back at the window and that same, heavy horror settles in my belly every time I look. After organizing the boxes and clearing out trash and wiping down surfaces, the only thing left for me to do is sweep before I’m done for the day.

I’m sweating with how much I don’t want to deal with this. I can handle a lot, but I don’t handle dead things well. A few months before this, I followed a nasty smell in the coffee shop to an empty cabinet where a rodent of some kind had keeled over. I had the community center director deal with it, as I waited outside until it was handled. So here I am, fixated on these once living things and trying to hype myself up to think of them as a pile of leaves so I can brush them into the dustpan and maybe head home a little early today.

My hands are shaking and it feels like I’m going to pass out, while I pull straw bristles through the square of dead butterflies. One of them twitches their wings, just a bit, and I let out a weird, mangled scream like Kermit the Frog and drop the broom while jumping back. Luckily, I’m alone and nobody witnessed me losing my shit over something obviously caused by the air being stirred up by the broom.

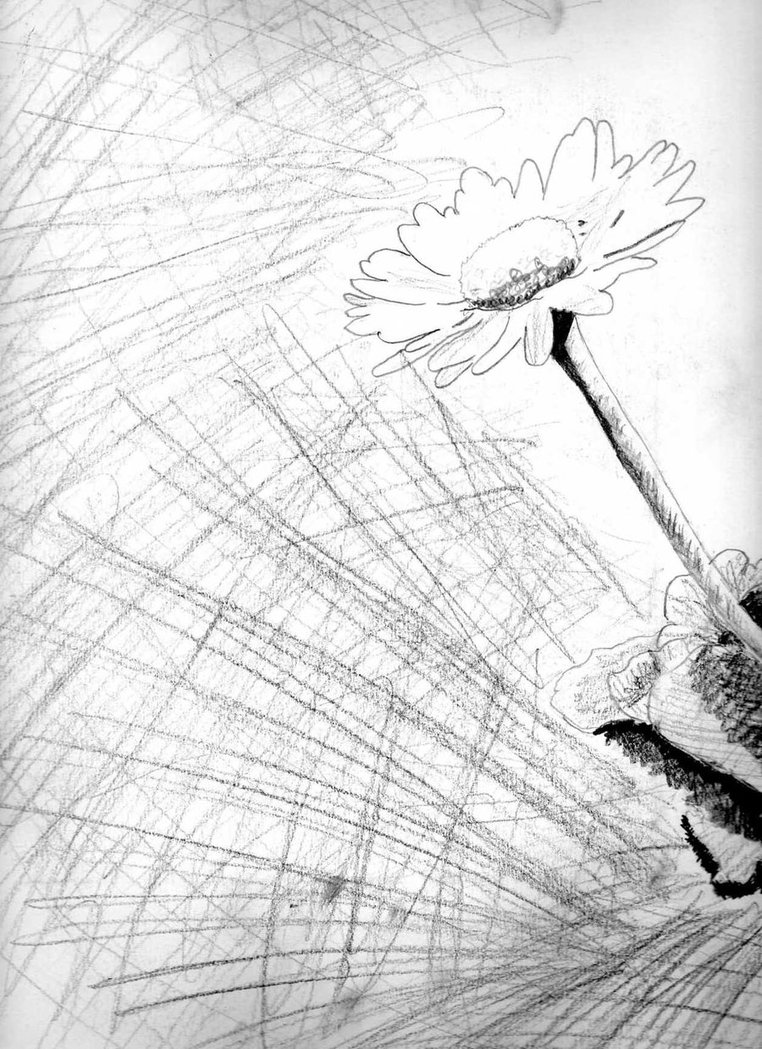

I pick the broom back up, doing that thing where you snatch something really quickly because you’re chicken-shit scared, and then take a second to get myself together for another pass. I kind of poke at the offending butterfly carcass with the broom and this time, the antennae and legs move along with the wings and it flops forward, legs weakly kicking out in the air in search of solid ground in a sorry attempt to escape the splayed-out bristles of Armageddon incarnate. Despite the fact that I’m completely sketched out, I squat to get a closer look at the thing. Most of the butterflies seem long dead. Their colors are faded and dull, but this one is now opening its wings fully, showing off deep orange, brown, yellow, white and black patterning. It is vibrant and alive—if only barely.

I don’t know what I’m expecting to happen when I lower the dustpan and slide it gently up to the butterfly’s forelegs. Slowly, unreasonably slowly, it places its two front legs against the lip of the dustpan and then stops moving. I wait a few seconds, but it seems like that’s as far as it’s willing to go. When I start to lift the dustpan a bit, it hooks its elbows over the lip and clings on like it knew I wanted to save it all along and it was just waiting for me to figure it out. Taking small, shuffling steps toward the back door, I watch the butterfly more than my surroundings while I walk. It doesn’t seem to have a great grip on the dustpan, and I don’t want it to be shaken off by any sudden movements.

This one won’t die without ever tasting air that doesn’t smell of dust and mildew.

We are just stepping outside when one of its little legs fails and it flutters violently down to the metal threshold. So close to freedom and now it gives up? I think it might be dead, or too far gone to save, but I nudge it with the dustpan and try to get it to crawl back on. It grabs hold, and I lift it a bit too quickly and it flops back off. I try again and again but it keeps falling off and I’ve really got to get back to work — I mean, at least its outside-ish. But still, its struggling and kicking its legs in a protest of life, so I have to give it just one more try.

This time, I waited patiently for it to fully grab hold and its grip is much fiercer than before. I walk even slower and pass between canoes lashed to the awning on my way toward a stand of birch saplings with low branches. As gently as a person can move, I set the dustpan against a leaf and hold my breath so that I don’t break the “docking” connection as the butterfly—which I learn later is a tortoiseshell butterfly—takes its sweet time extending each leg and placing them on the leaf. When it’s finally completely clear of its plastic platform, I step back and watch it bask in the sunshine. It opens and closes its wings as slowly as it does everything else. It’s probably getting accustomed to the resistance of the slight breeze after a lifetime of stagnant air. Probably won’t survive long, but this still feels like a victory.

I take my time going back inside. The boathouse seems purer now. Cleansed and a little holier than when I found it. I’m ready to get back to the task of sweeping up. Almost immediately, another butterfly is roused from its catatonic state. Then another. I squat down close to the ground again and gently blow on the butterflies to see if it’s possible I’ve been wrong about them all being dead. The hope is dizzying. But, no, most of them are basically like fuzzy little scraps of tissue paper with torn, colorless wings. Only these other two butterflies are still clinging to life, and who am I to deny them a chance?

It takes a good fifteen minutes to move both butterflies. Their companion is still sunning itself, and I do my best to be careful while placing each of the butterflies on their own branches so as to not knock any of them off of their perches. One of them has a torn wing. Satisfied that I’ve given them the best possible chance, I head once more back to the boathouse. I carefully check all the butterflies one last time and sweep the remaining husks out the back door with complete awareness that I’ve just spent a half an hour saving three butterflies while on the government’s timesheet. I’m okay with that. There are worse ways the Federal government could spend $6.