by Evan Nasse

A Cinephile is defined as, “A devoted moviegoer, especially one knowledgeable about the art of cinema.” It is this definition that has been falling slowly by the wayside as Hollywood adopts a business model of finding profitable, “entertainment,” and moviegoers becoming apathetic about what they view. The problem goes deeper than that if you look at cinema over the last ten years, compared to what you would find in cinema from fifty years ago. Several publications discuss the decline in film quality as a whole. Some writers on the subject are calling it, “The Death of Cinema,” who believe cinema should be given up, that there will be no classical artistic films ever made again. The outcome for the future of cinema, especially cinema as an art form, is a bleak one to be sure. The only people who disagree about the current declining state of film work in Hollywood; the ones who are reaping the benefits of churning out the same action movie year after year. Producers and directors like Michael Bay, Steven Spielberg and James Cameron are unapologetically calling their most recent works, “masterpieces,” and show no remorse for current Hollywood trends such as blatantly declaring protagonist/antagonist as early as possible followed by action/chase scene abruptly followed by hammed up dialogue/love scene and finalizing with a cliché and predictable final fight sequence/grandiose battle scene.

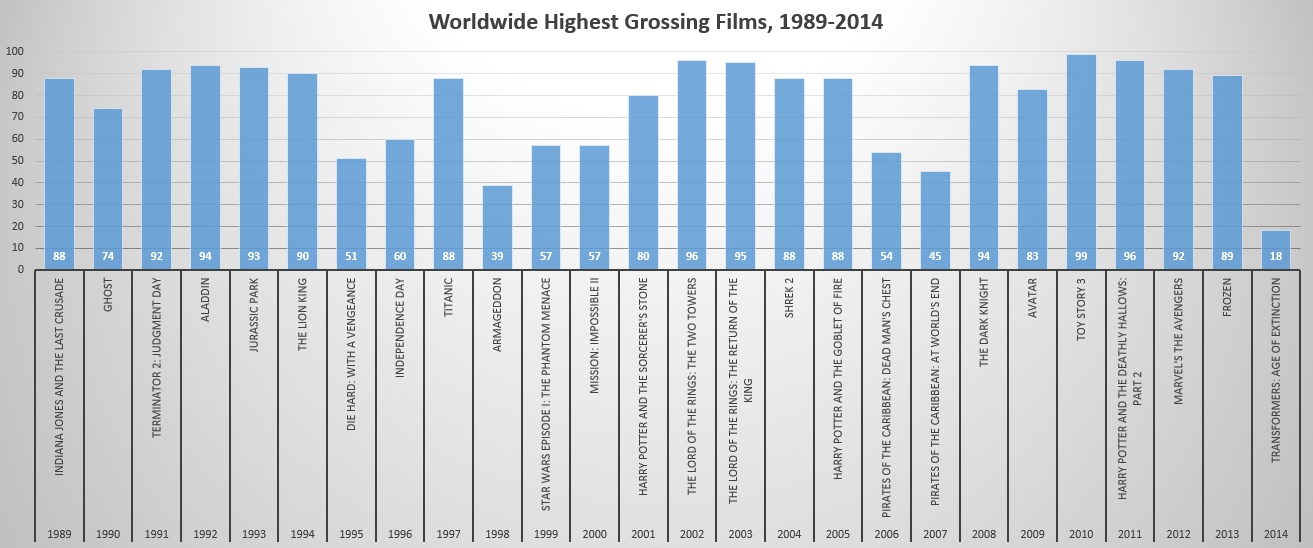

The debate of cinema’s decline began when Susan Sontag wrote her acclaimed article, “The Decay of Cinema,” wherein she points out the loss in quality of film over quantity and big budget special effects (decline had been noted by many fans and film critics) before Sontag’s groundbreaking piece, but it opened many new eyes to the lackluster projects. For many years the Hollywood business model has been to try to top the most recent film that scored big at the box office, and when looking for material to imitate, the studio producers and executives have gone the route of mass market appeal, and iconic or popular actors, they dedicate most of the work on the film to special effects teams and promotion. Sontag also points out in her article what she calls, “The catastrophic rise in production costs in the 1980’s,” which led to a globalization of movies that demanded more profit for bigger budgets, in turn demanding more profit to get a bigger budget, and so on. This further perpetuates the reduction of time, energy and investment in the film itself, relying on its promotions and product placement tie-ins rather than the development of the story and immersion for the audience.

The lack of dedication to good storytelling has led to the suffering of scripts, further leading to the suffering of character development that converts to poor dialogue choices, which affects acting and actors. Dialogue—good or bad—is cheap and easy to create for up-and-coming screenwriters trying to get their scripts through the door of Hollywood’s close-knit culture. It is implementing it that has fallen by the wayside. You can point to nearly any recent action film, and among its features you will find several gaping plot holes (rather than create an engaging dialogue, monologue or explanation, an action scene or chase scene will take its place). This directive action further downplays any connection an audience might have had with any of the characters on screen. No longer are modern cinemagoers interested in the tale of the downtrodden, the everyday schmo. Self-involved dramas have fallen to the side of the road like a neglected child. Modern films have nearly made it a point to disassociate themselves with realistic films dealing with real world drama; big budget films need only a silent protagonist that shoots big guns.

In Heather Hendershot’s article, “Loser’s Take All,” she further adds that this was no mere incident of Hollywood’s disconnect. Studio megacorporations keep their pulse on rising stars, directors and writers, always looking for a new source to exploit. The beginning of a majority of film’s most prolific directors come from humble, independent films who made their debut doing small budget films primarily dealing with social commentary through down-home characterization. Stephen Spielberg became noticed in Hollywood when he did Sugarland Express, a film about a down-on-her-luck blonde who is released from prison, and upon learning her child will never be released back to her from the state, she convinces her husband to also escape from prison to kidnap their child, a stark contrast from the next film he directed, titled Jaws, which is believed to be the original big summer blockbuster film. Jaws premiered in over 400 theaters in the United States alone and was a box office hit worldwide, and from that point on Stephen Spielberg’s direction and production range from art pieces like Saving Private Ryan to generic CGI action schlock like War of the Worlds and Minority Report, which he uses to bankroll his other film projects. Hendershot mentions the attempts made by a few actors and directors who tried to take back the direction of modern cinema, such as Dennis Hopper and Peter Fonda with Easy Rider and other small independent films viewed by the old-boys-club in Hollywood as “hippie films.” She goes on stating; “…the suits ended up hiring longhairs because they made movies that were popular,” further reinforcing the attraction independent films have to audiences, followed by their induction to major box office companies. Inevitably the affair with socially commentative films died once the box office mega hits came around, according to Hendershot:

…Jaws had already given the studios a lucrative formula for making movies, one that George Lucas was quick to capitalize on with Star Wars. The outcome was inevitable: By the early 1980’s directors had lost control over pictures, individual artistic vision had been pummeled by a blockbuster mentality…

With the advent of the major Hollywood blockbusters came the inevitable stage of where to turn to next. Directors and executives quickly realized that source material would quickly dry up for action and blockbuster hits when all artistic vision had been essentially thrown to the wayside. Style over substance leaves you quickly scraping the bottom of the barrel. That was when studios turned to another medium already well established, one that was even written out for them in a scene-by-scene breakdown with a storyboard and dialogue; action based comic books and graphic novels. Matthew McAllister points out in his article, “Blockbuster Art House Meets Superhero Comic…” several of the contradictions in Hollywood’s mimicking of comic books in film—whereas modern blockbusters are rarely character driven, almost all comic books and graphic novels are solely character driven. The initial success from 1978’s Superman movie was no incident. The initial drumming up of press for the movie started with the hiring of noted actors such as Marlon Brando and Gene Hackman, and it also received the same amount of press time, commercials and interviews Star Wars and Jaws before it did. It also helped that Superman as a character had been widely established and incredibly popular well before the film even began its first draft of the script, borrowing heavily from older story lines already in place for said character. The essential mould had been made. Now all Hollywood had to do with their new cash cow cookie cutter was to pour in the money, advertising and special effects, and then laugh all the way to the bank. This cycle of film making becomes very apparent, with more recent films such as all the Superhero movie sequels and action sequels sprouting up, showing how Hollywood has a more vested interest in making X-Men: Again and The Fast and the Furious 15: Furiouser, rehashing the same plot rather than picking up a new intellectual property featuring character driven narrative and little to no special effects.

All these factors have lead our rich cinematic history resembling a pointless competition, with the consumers and viewers being the losers. Hollywood has tried time and again to top itself with big budget blockbusters, trying to figure out some strange code for how to make a billion dollar profit film. Meanwhile, they’re actually just hammering puzzle pieces together in an attempt to make them fit and testing the results with our ticket stubs. In his article, “The Worst Movie Year Ever?” Joe Queenan points the critical finger of blame to the consumer. Year after year we stand in line and hand over our hard earned money for half-assed cinema in hopes of being entertained and walking away disappointed that we received the same film we did last year but with different actors or a slightly different plot or action scene. There is a certain degree of detachment for critique. For certainly a children’s film shouldn’t be held up to the same critical judgement as an action film or a drama, but nonetheless those are also being dumbed down with promises of marketing potential for studios or advertisements on Mountain Dew bottles. Personally, I use such marking as a guarantee for a film to be unworthy of my investment of time or money. When I see Vin Diesel’s face on a Dr. Pepper bottle with his latest movie’s name on the side I know to avoid it. In Queenan’s first sentence alone he summarizes how I feel year after year when I see upcoming previews in a movie theater:

In a millennium that has thus far produced precious few motion pictures in the same class as “The Godfather,” “Jurassic Park,” “Casablanca,” “Gone with the Wind,” “My Fair Lady” and “The Matrix,” there is a knee-jerk tendency to throw up one’s hands and moan that the current year is the worst in the history of motion pictures.

It leaves a cinephiliac embittered knowing that the best they have to look forward to is roughly a handful of good movies a year, if any at all. Moreover, it leaves one wondering where all the magic in movies has gone; the mystery of how something was filmed is now replaced by CGI after effects. Where once Sigourney Weaver had to confront the terrifying xenomorph, dripping acid and twin jaws clasping for a place to puncture her chest as it would rend its victim in two, now it is replaced by a green screen and a man in a green suit covered in goofy trackballs, removing all ability to suspend disbelief in monsters. All these factors have culminated to a degenerative cycle removing any resemblance of art in a medium with a secure foundation in artistic license. In a civilized society we are quickly devolving to wanting mere entertainment, regardless of thought provocation or content, thus creating a profit only based major film industry that will eventually result in the loss of storytelling in cinema as an art form.

[divider]

About the Author: Evan Nasse is currently in his senior year at APU and is co-editor for the Turnagain Currents. He enjoys reading far too much Stephen King. He prefers writing short stories and screenplays with a predilection towards horror, science fiction, fantasy and comedy.

About the Author: Evan Nasse is currently in his senior year at APU and is co-editor for the Turnagain Currents. He enjoys reading far too much Stephen King. He prefers writing short stories and screenplays with a predilection towards horror, science fiction, fantasy and comedy.

4 Comments

Ian McDermod

Movies and the art of Cinema has very much changed over the last 20 years. I agree with many of the points you make in this article, especially the rehasing of big action blockbusters. It seems like nearly every comic book hero in existence gets his own movie now in an effort to make a multi-million dollar box office smash all featuring the same overdone CGI and the mundane superhero plots. It seems like very few focus on the art of good cinema that includes masterful storytelling, characters, and rich cinematography. Instead people go to the movies to see the next big installment of a superhero character beacuse that is what everybody will be talking about next week.

konveksi solo

Hi there, everything is going nicely here and ofcourse every one is sharing facts, that’s really fine, keep up writing.

data recovery file

Wonderful when I see this. I can get many useful information. Hope more communicate we can get with each other. I wish to apprentice while you amend your web next time.

3w3u.header.us

Beware the man who wants a position in your life wherein he can sabotage your livelihood, income, or projects. You’ll know the signs. Don’t give him trust.