By Rosanne Pagano

Because Justin was small for having just turned 8 and because he had gotten good at anticipating most of the bumps on weekend drives up to the Connecticut countryside, he could readily and regularly lift up from the Pontiac’s deep backseat to peer into the front, where Nana Mary sat behind the wheel. The speedometer was green, the color of a dragon’s scales, and the needle now read 70 MPH. Justin’s lifting up worked especially well when the Pontiac had left the city streets and turn on to the Merritt Parkway, a long thoroughfare of few but very enjoyable bumps. Following a ribbon-cutting the previous summer, a gathering of New England bigwigs attended by Justin and Nana Mary, the Merritt had fast become the dream of non-New Yorkers who relished a day in the city but disdained the train. Wasn’t it always so hot and crowded! And littered with other people’s forgotten things, to say nothing of the deep dents left by rumps untold.

No one had to explain the pleasures of the Merritt to Justin; he was quiet but clever, small but observant. Every Friday at noon on the dot he was loaded into the backseat of Nana Mary’s Pontiac and driven west along the Merritt, left to himself in the engulfing backseat to consider the virgin stands of maple and elm whizzing by to left and right. Nana Mary spent her weekends in the country, overnighting at the large, echo-y houses of old friends, and Justin went too. On Sundays they drove back the way they’d come and Justin was deposited at the scrubbed marble threshold of his mother’s upper East Side apartment. “By bedtime, please,” his mother, Nana’s only daughter, would say, waving them off from the sidewalk, glad to see her boy, her dearest and only child, enjoying himself. How Justy loved getting out of the city! How he loved his nana! But as far as Justin could tell, the hour he was expected home — returned once more to the big-shouldered brownstone and brisk doormen — the hour of Justin’s bedtime was inexact.

Sometimes the Pontiac pulled up so late on a Sunday night that his mother, blonde one month, brunette the next, was already asleep; other times Justin was returned at dawn. Like all children he had come to understand that adults make rules for the joy of breaking them.

“Nana Mary, I’m hungry,” Justin announced from the big backseat. “I’m hungry now.”

“You’re always hungry,” his nana said, gazing up into the rearview mirror. “Let me know when you’re not hungry, Justy.” She laughed. “That’d be worth pulling over for. Taking a snapshot of.”

Justin did not like being called “Justy.” It sounded a little like “fussy,” which he was but did not like being reminded of. “I’m hungry now, Nana Mary.”

“How about a nice sandwich?” Nana Mary said. The speedometer did not drop a fraction — there’d been a small bump and Justin had lifted up to read the numbers. They were bright yellow, the color of urine when they gave you too much penicillin. The speedometer glowed 75. Outside the window, trees in autumn flame flew past.

“A sandwich, Justy?” Nana Mary repeated. “Doesn’t that sound good?”

It did not. What Justin had in mind was a certain diner — he believed it was just this side of New Canaan — where they served steaming corn niblets and macaroni and cheese with cut-up hotdogs tossed in.

“No,” Justin said.

“No, thank you,” said Nana Mary. At 80 miles an hour, the car’s massive chassis felt fine and sure, swift as the pointy sculling boat that had defined Nana Mary’s college days when, firm as a springtime reed, she would slip into her seat among the other girls to pull long and hard to the finish line. And those days weren’t that long ago, not really. The parkway was a godsend. Behind the wheel of a good car on a sunny day on the Merritt, Nana Mary felt delivered of every worry, every unpaid bill and both ex-husbands. Driving to the country, she could distance herself from balding bankers and young accountants and pretty much every other man in her life. Little Fussy Justy included.

“I could live on sandwiches,” Nana Mary said. “In fact,” she continued, “if you can guess where the picnic basket is — and it’s a big car, Justy, so keep that in mind, lots of hidey holes! — if you can guess where Nana hid our lunch, we’ll pull right over and you can have a sandwich. There’s egg salad and roast beef and pickled –”

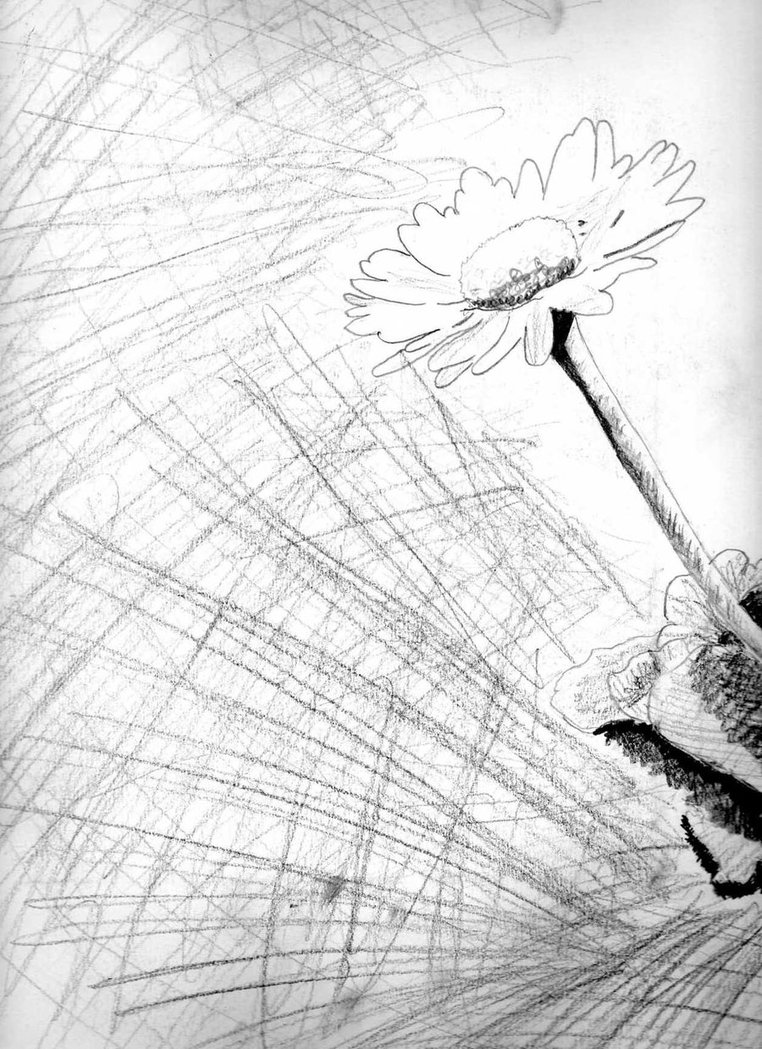

“You sound like Ratty,” Justin interrupted. It was getting to be a habit. “You sound just like Ratty and Mole in the boat, when they pushed off from Ratty’s house along the riverbank and Mole wants to row but he can’t. Ratty tells all about the food he packed and then Mole says, ‘Stop, oh, please stop,’ because it all sounds so so delicious.” Just then the boy ran out of breath and a good bump raised him up without his even working at it. The speedometer said 83.

“Yes, indeed, I could live on sandwiches,” Nana Mary said. From the backseat, Justin had raised up so high that now he could see directly into the rearview mirror. His grandmother dreamed of sculling, of sandwiches. Her eyes were closed tight.

And because Justin had made no effort, none whatsoever, to sniff out the neatly packed basket ordered that morning and charged to Nana Mary’s account at Danito’s on East 52nd, she suddenly reached back, up and over the tall front seat, to dangle her right arm from the elbow down and point a slim finger to the spot where the hamper had been tucked beneath a stable blanket. Bits of hay had stuck out like quills until one by one Justin plucked them from the blanket, thick as a hide, so that hay now lay scattered where his feet would have been if they touched the backseat floor.

“Look right there,” the old woman shouted, just as she took a final curve, that smooth, long, crimson-leafed last curve just before New Canaan, the curve Justy had seen coming because he had raised himself up and tried to shout back, not waiting for the bump that did not come.

(END)